What we mean by resources

Inventory, staff knowledge, that special something that makes your organization unique - each of these things are examples of resources, and ones that are essential for your organization to do what it does best. At the same time, there are many other resources that are essential for your organization to succeed that are not as obvious, visible, or measurable. Our custom approach to input evaluation helps shed light on these essential resources. To help you understand how we create value, we want to establish some important definitions.

What is a resource?

At Inluminare, we define a resource as an asset controlled by a firm, or everything that an organization controls and uses in the process of delivering some kind of desired output. This includes physical items and buildings, employee knowledge and skills, and how your organization is set up to be successful. 1 We try to get as precise as possible: specific skillsets over job titles, brand names and model numbers over “just an oven.” This allows us to tease apart which resources were most important for your success and which could be replaced to improve your outputs. In other words, we see resources as the inputs used by an organization to produce.

What is an input?

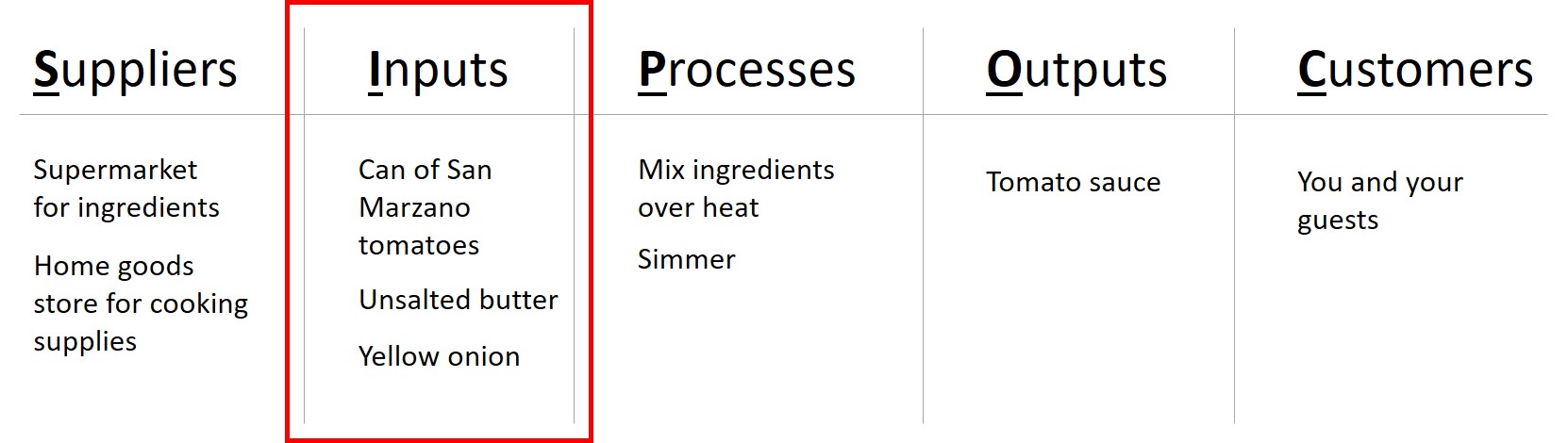

We refer to inputs as what is consumed during a process to achieve a desired output. For example, if I am making a tomato sauce,

- the output is the completed, ready-to-eat sauce,

- the process is assembling the ingredients, cooking, and mixing as appropriate, and

- the inputs are the ingredients, the recipe, the various cooking tools, and other knowledge about what makes a really delicious tomato sauce (we recommend this three-ingredient recipe!).

When we want to understand how much we spent on achieving our desired tomato sauce (or a different output) and what are some adjustments we can make to have it be even tastier, having a complete catalogue of all of the inputs allows us to make refined, targeted decisions about areas of improvement for the future.

Why not focus more on the process?

There are many tools that focus principally (and some exclusively) on processes that also address inputs and resources, but all leave something to be desired. For example, a SIPOC diagram is a way to visually capture how we produce a pizza, but because the focus is on the process, the full range of necessary inputs is often left unaddressed. In fact, the common guidance when creating a SIPOC diagram is to focus on the raw, physical goods that are most important to your process!

In the diagram above, you can see how a SIPOC diagram and similar tools can be instrumental in helping you begin the process of what resources you will need to produce a particular output. But, as we see in the red box, we lose detail in identifying all of our resources. It could also be that there is another essential resource that we should include, but we will only discover this once we have actually made the sauce – such as a sauce pan!

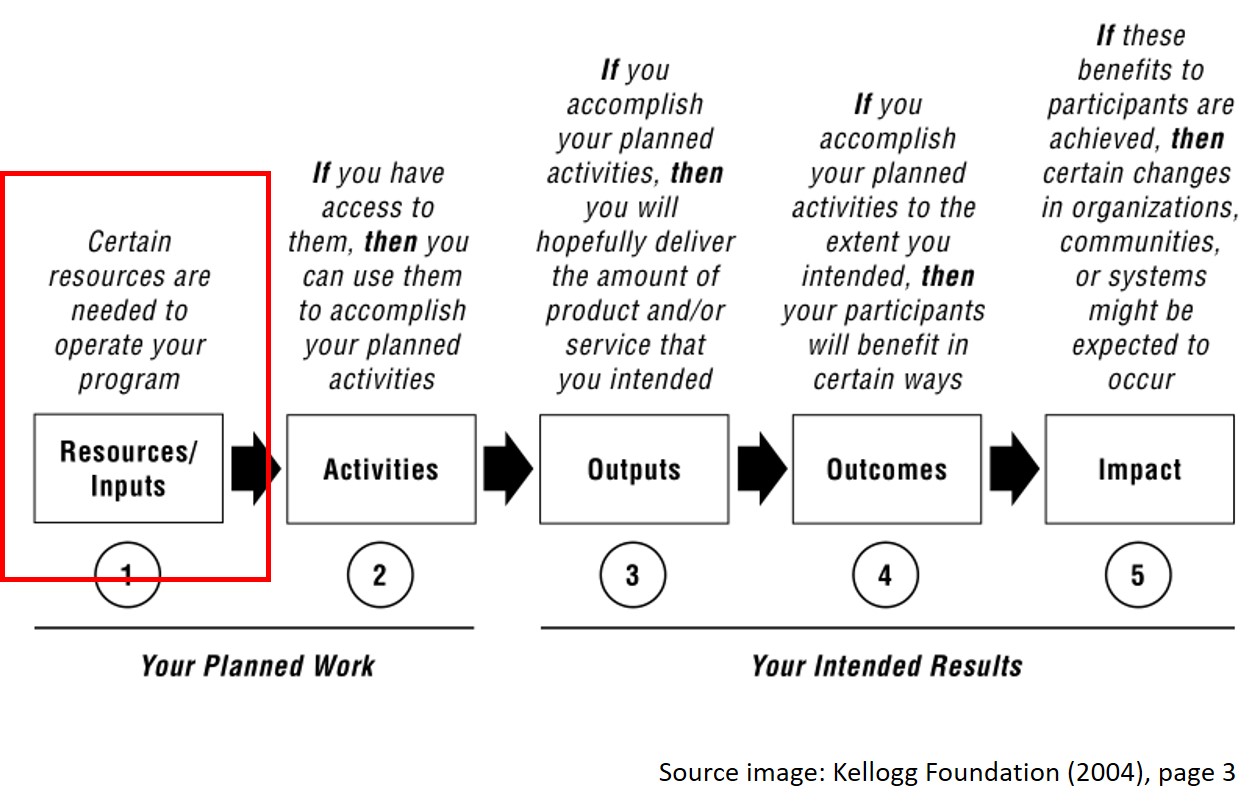

For nonprofits and government agencies, a similar tool is used before starting a project to establish an expected “theory of change,” or what needs to happen in order for something in society to be different. This is often referred to as a logic model, a visual representation of the various relationships between our inputs, processes, outputs, and desired short- and long-term outcomes.

The logic model above is an excerpt from the Kellogg Foundation’s “Logic Model Development Guide,” commonly used to establish best practices of what a logic model should look like or accomplish. The red box captures how resources are the first step in any effort to produce outputs and achieve some kind of outcome. At the same time, it is only meant to capture “certain,” major resources – ones that are obvious beforehand but, again, may not prove to be as important in retrospect.

Timing matters

The two tools shown here have something in common, along with many other, similar methods: they take place as part of the planning before the work gets done. What inputs are necessary for the different activities or processes to produce intended outputs is driven by historical knowledge – knowledge that we bring from similar efforts, previous employments, or past versions of this process.

A critical component of organizational learning is to understand what is happening in real time and after the fact, to monitor and evaluate, and to collect data and insights to inform future decisions. These actions provide critical opportunities to reduce costs and be more effective, while also increasing efficacy through getting closer to producing our ideal output – from a watery, burnt tomato sauce to one rich in flavor. This is where Inluminare shines. Through our products, we provide you insights on the resources that you used and intend to use again, focused on:

- Fair market valuation: what is the price someone would pay for the resource in a competitive marketplace? This is the number that important standards-setting organizations want to see.

- Non-financial valuation: you can choose from a number of different ways to rank, measure, and categorize resources, to gain insights on what is truly essential versus what is just expensive to acquire.

One of the sources that we used for this definition is Jay Barney’s seminal 1991 article, “Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage.” The author goes into detail, describing resources as

* firms’ strengths;

* “all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc.;”

* and falling into categories of physical capital, human capital, and organizational capitalSee Barney (1991), p. 101, section “Firm Resources,” for the source of the quote, more detail, and further reading. ↩